Clean Meat and the Future of Food

Beyond Meat’s ridiculously successful IPO has turned the attention of both VCs and Wall Street to the intersection of food and technology once again. The achievements of the founders of these companies are genuine, and the business is both impressive financially and a step forward to a better food system.

Their success is built not just on a series of technological innovations, but also on something even more interesting- the positioning of their brands and products in such a way that their products have both economic and cultural value in the minds of consumers.

I think it's important for future entrepreneurs to really understand this innovative way of branding food products, and to understand what the context of these companies are in order to be able to create more great companies who win over consumers.

Food Fight

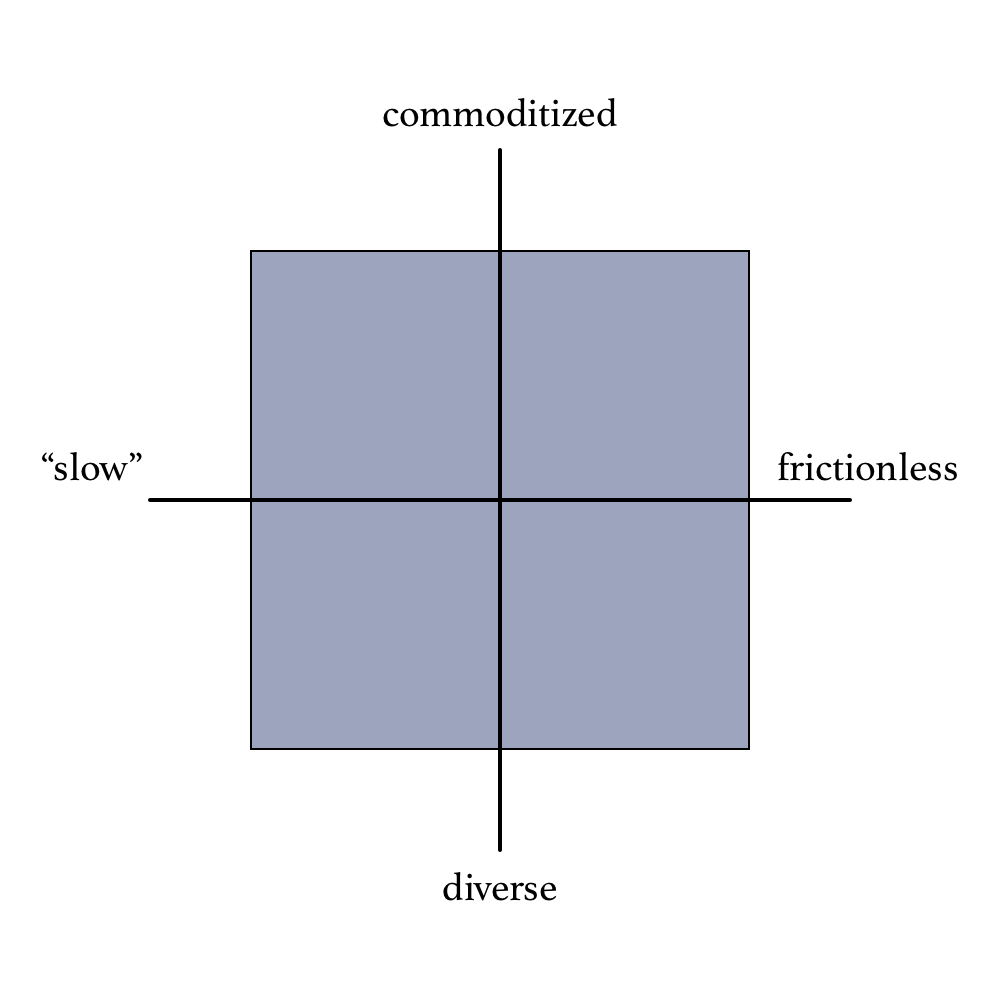

In early 2015, my first ever published piece of writing helped folks understand the future of food systems with a simple 2x2. I’ll link it here, and provide an excerpt below for those who want the Cole’s notes:

The Quadrant Thesis of Food Systems

For an absurdly long time, food was slow and diverse because that's how you made sure you didn’t starve. Diversity meant that if climate was particularly brutal in one direction or another, you didn’t lose all of your growing crops, just a subset of the total calories available to you. Slow was a necessity because the industrial revolution was very late to food.

From 1945 or so onwards, two guys really pushed agriculture out of the lower left corner- Norman Borlaug and Earl Butz. Driving science and policy respectively, they drove us towards a modernized, commoditized, mechanized food system.

Starting in about 2000, America started to get suddenly suspicious of the food coming out of that top right hand corner. Highly commoditized, frictionlessly delivered calories started to look like a good way to get sick and die young. We started to panic, and to reassess.

by 2006, we had The Omnivore’s Dilemma and Slow Food USA. Slow Food arose as a reaction against the impossibly quick calorie delivery systems we were eating, and Michael Pollan effectively questioned the role of the big commodities in our food system (corn, specifically).

Suddenly, there were two camps- the mainstream food system eating commoditized, frictionless food, and the Pollan camp eating “slow”, diverse foods that were the antithesis of this movement.

From 2006 onwards, innovation in either of the two camps was becoming more and more difficult- creating “slow food” that was better than what was being served in high-end restaurants seemed impossible, and creating “fast food” that was cheaper than what you could get at McDonald’s seemed impossible.

From 2006 to 2016, our food innovation has mostly been in the two other camps-

fast, frictionless services in food that offered more diversity in both ingredients and selection.

highly commoditized foods that were connected to the values of “slow”.

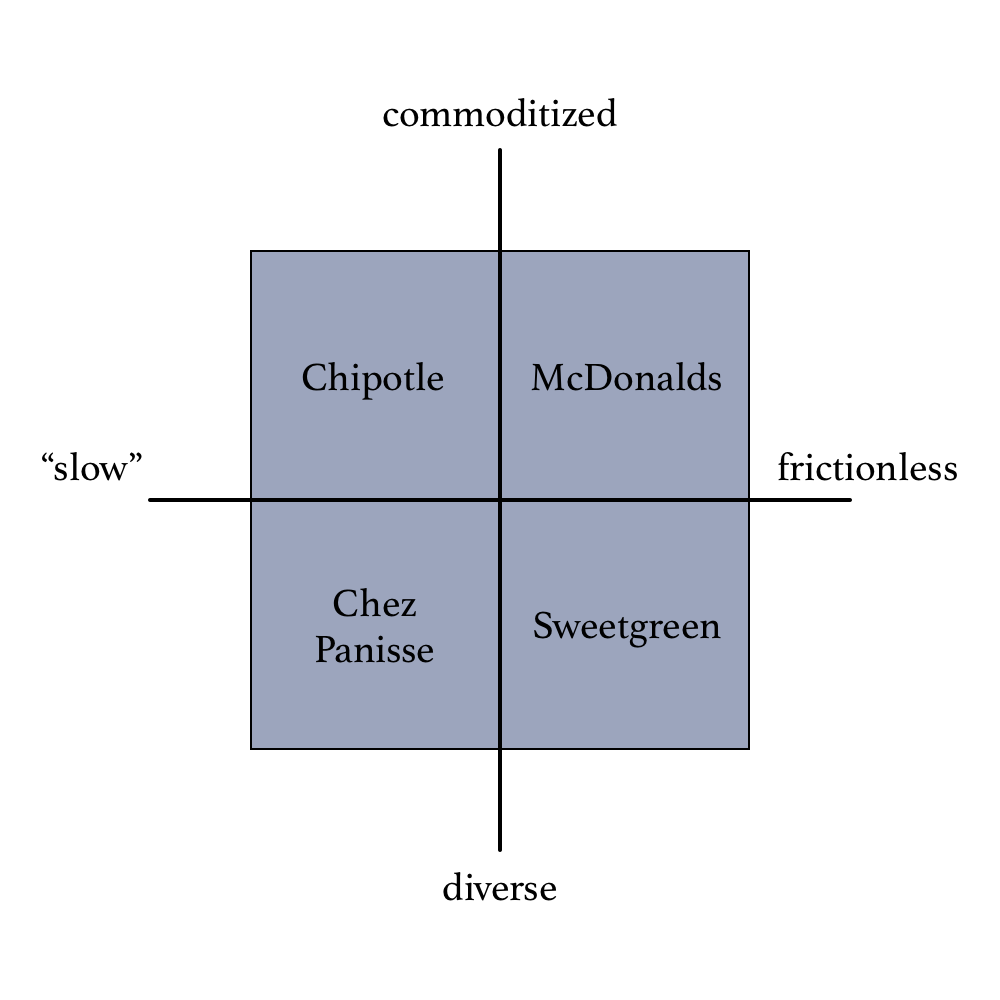

Some amazing businesses have been built in the top left corner and bottom right, respectively.

Chipotle proved you could make food values-oriented and “slow” while selling commodities- their menu is still basically corn-based, but better corn. Corn fed to animals outside. Corn rolled into healthier shapes.

Sweetgreen and others have proved that diversity can be bundled and delivered at high-speed and low-friction through innovations around the supply chain and a focus on selection over price.

Alright, you’re caught up on the quadrant thesis- now we can proceed to look at this from the perspective of plant-based meat discussions.

The heart of the thesis is that the two camps inside of the food system each won only half the war for the future of food.

Big, fast, commoditized food won the economic war. Slow food and diverse systems won the cultural war.

Fast Food Wins

Putting aside government subsidies, sustainability questions and ethical quandaries, the industrial food system has triumphed over older, diversified systems in its ability to deliver fast, frictionless calories to the mouths of hungry consumers.

The evidence is everywhere- the success of fast food expansion into the developing world, the creation of new brands in the fast casual space, and the resistance of many commodities to the rising cost of food globally.

The ways that these companies won this war for American wallets over the last 30 years has been described in a myriad of ways over the last decade in print and screen. While we have hundreds of stirring documentaries telling us that small, diverse food systems are still fighting, it's rearguard action at best. Slow foodies have been left clinging to their kale and moral superiority with between 2-5% of the American spend on food. Big Ag won.

Slow Food Wins

In a sharp contrast, however, it is brutally clear to anyone who has ever picked up a food magazine or gone to a farmer’s market in the past decade that slow food has won the culture war. There is a complete distrust of the commodified industrial food system that has led to endless waves of consumers moving away from it in favor of supporting localized, diverse and meaningful food in their communities.

The culture of food is moving in this direction, and there is little evidence that this trend is slowing down. Even the most “commodified” aspects of local, diverse “slow” food systems, like Whole Foods, now owned by Amazon, still take great care to brand and market their connection to the winning side of the culture war.

Plant Based Meat & Consumer Perception

Enter Beyond Meat, Impossible Foods, and others. They are the darlings of both the culture war of food and the commodity giants of food- a seemingly perfectly executed feat of marketing genius. These brands have been able to situate themselves inside the minds of consumers as “slow” food without having to drop even a tiny iota of the industrial, commodified advantages that are inherent in their model. This category should shine bright in the minds of any and all who are interested in the creation of new and exciting brands in the food and technology space- food that is on the winning side of both the culture war and the economic war.

How They Did it

The reasons that consumers favor local, diverse and sustainable food systems lies in the simple fact that chasing the most efficient ways to create fast, cheap calories have led to massive and dangerous externalities in our world. The obesity crisis, the lake of algae at the mouth of the Mississippi river, the horrors of concentrated animal feeding operations and a dozen other awful goings-on around the globe have led millions of people to reject commodified food and have led to the triumphant gains that “slow” food advocates have long sought.

The genius of plant based meat lies not in the embrace of these ideas of slowness, diversity, and localization of food (indeed, the success of these products in creating a new premium category that is non-local and non-diverse will be a tremendous detriment to “slow” food) but instead the ability to manage these externalities. Put more simply, these products default to the “slow” food part of consumer preferences not because they belong there, but because most people can’t figure out a reason to put them anywhere else.

These products use less water, less land, don’t torture and kill living creatures, contribute meaningfully to Climate Change, or create vast lakes of manure. They suggest themselves as a substitute for fast, commodified food that normally would attract the eyes of a typical consumer.

The Virtues of Going 100% of the Way

An interesting backdrop to this new food revolution is the various efforts over the last three decades for fast food and large institutions to substitute plant protein for meat protein.

There is a veritable graveyard of R&D, marketing, and government dollars that have gone into the development of plant-based meat substitutes, from McDonald’s and the “McLean Deluxe” to Taco Bell and their “Taco Meat Filling” to the Illinois Correctional system, who were sued over the large amount of meat substitute with soy protein that was allegedly making some prisoners sick.

The case for this change was not grounded in environmentalism, but rather economics and health. Meat is both expensive and high in some of the fats that traditional dietary guidelines have long regarded as bad for human health (meat-based diet people don’t @ me, I know, I know).

Simply put, we’ve been substituting plant ingredients for meat protein in the North American diet for many, many years; what these initiatives lacked was the courage to go all the way.

Beyond Meat, Impossible Foods and their many competitors were able to seize such a large and impressive market share from the meat industry in such a short time not because they were replacing some meat with plants, but because they replaced all the meat with plants without making it into a foreign taste or “veggie burger”.

This is a simple change, but powerful in the minds of consumers- you’re not eating something that you like that is cut with something you’ve never tasted before- you’re eating something totally new, unique, and critically, something that feels like you’re making a good, environmentally conscious, healthy choice.

A simple thought exercise makes this easy to understand-

Would you eat a Big Mac that was advertised as “55% beef” ?

How about Impossible Foods or Beyond Meat burger that was advertised as “2% beef” ?

Yet, most Americans would be happy to eat either of these things on their own.

Bringing It All Back Home- Culture VS Economics

For the moment, these products continue to perform a modern food system miracle- they enjoy the economic advantages of fast, cheap commodity food, and the cultural advantages of the Slow Food revolution. They enjoy a privileged place inside the minds of consumers as a wonderful addition to the old dichotomy of veggie burgers and meat burgers, and for the moment, are sitting pretty inside both these two camps, enjoying the advantages of both.